The following interview was published on the blog of Spanish retailer, Vila Viniteca. You can read the original post in Spanish here.

What is the current state of Spanish wines in the United States?

Curious but cautious.

Curious? How?

More and more Americans are traveling to Spain and there is an increasing interest in Spanish cuisine and regional wines. When I meet people who have returned from Spain, they tell me that they had no idea that it was such a large country – it’s more like four countries when you travel from Galicia to Barcelona with different languages, foods, tradi-tions and wines. It seems that everyone who visits become ambassadors for all things Spanish, much like the American love for Italian food and wine. The main difference is that Italy is fairly well known due to the immigration to the US from there a hundred years ago, but there was never that level of immigration from Spain into the US, so Spain is new, novel and exciting.

How is it cautious if there is all this excitement about Spain?

For many years there was little general knowledge about Spanish wines in the US apart from Rioja or any number of inexpensive import labels with good press – in essence the perfect combination of price, presentation and press. Most of these wines taste like they could be from anywhere, so they really did nothing to advance knowledge of Spanish wines apart from giving most people the impression that they are inexpensive and easy-drinking. At the same time, there is this broad consumer awareness for Rioja. Press and presentation have always been less important than price for Rioja – with the exception of a few blue-chip estates like Lopez de la Heredia, Artadi, La Rioja Alta or Benjamin Romeo. It’s Bordeaux-like in that regard. Both of these categories of wines, Rioja and value Spanish wines have permeated the US market, even the heartland. They are both dependable but don’t tell the full story of the diversity and excitement that Spanish wines offer.

What can be done to tell the full story of Spanish wines?

There is new group of Spanish wines, what I like to call wonderlust or wanderlust wines. These wines appeal because they are novel – they come from emerging regions or show a new take on a well-known region like Olivier Rivière in Rioja or Dominik Huber in the Priorat for example. The most intriguing of these new wines are made with indigenous varieties and aged with little or no new oak, or in concrete vats, or amphorae. These transparent and authentic wines appeal especially to younger wine drinkers who are more willing to experiment with regions and varieties that are unknown to them – they want a new experience, they want to taste the vineyard in the wine, not the cellar. These are exciting wines for them, and for me.

Dominik Huber, Les Tosses, Torroja

Have you always had a preference for indigenous varieties, if not the downright obscure?

When I started my company I followed my own curiosity. I was always more drawn to satellite appellations or backwater places that didn’t even have official appellation status so I’m happiest looking for new wines and new properties that are far off the well-beaten track. I feel the same passion for indigenous varieties. I’ve gone from Albariño, when I started with Spanish wines to Albillo today– from Albillo to Verdil! Probably the best example of this embrace of indigenous varieties, is Pablo Calatayud.

Pablo Calatayud, Monastrell, lagar

Of Celler del Roure in Valencia?

Yes, when I first started working with him, he was already championing Mando at a time when most of his neighbors were replacing it and other indigenous vines with what they thought were more commercial grape varieties. It is a shame, as Valencia is ground zero for some of the most creative cuisine in Spain right now, but most estates in the area seem more interested in bland and commercial wines. So first it was Mando, then the restoration of his old cellar of subterranean amphorae for the aging of his wines, then employing his ancient stone lagars and now he’s seeking out other indigenous varieties like Verdil and Valensi. There’s still debate on whether the Valensi is in fact Tortosina but both these varieties are ancient and have a long history in the region. His wines speak strongly of place because they are so honestly made and these are the sort of wines that speak to American wine drinkers interested in being transported to Moixent when they open a bottle of his wine.

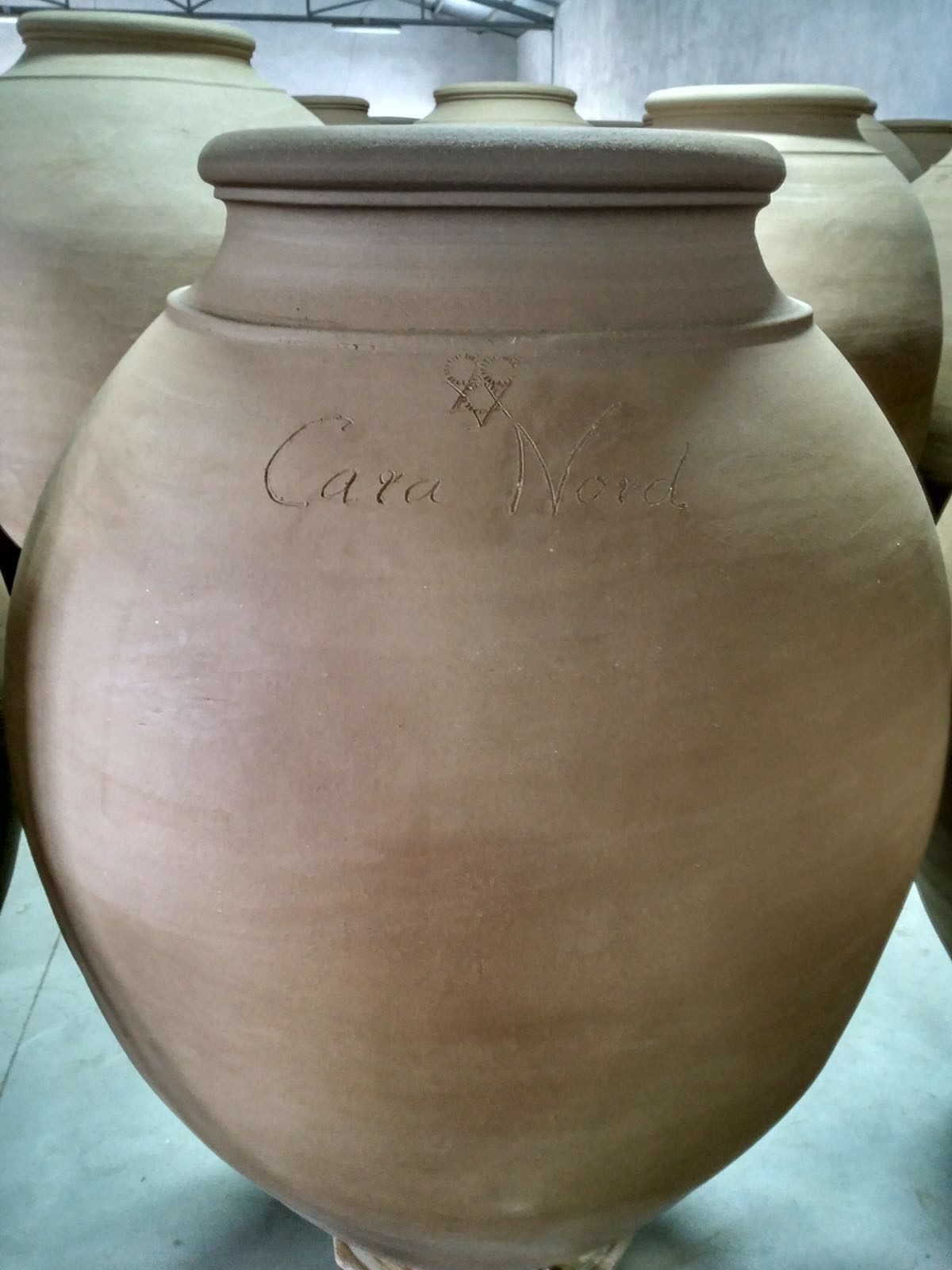

Inspecting new amphorae for Celler del Roure

Isn’t the movement towards amphorae aging in Spain is in fact a return to an indigenous way of making wines?

In a roundabout way, yes. Obviously there are the ancient cellars at Celler del Roure with many of the amphorae still intact, but it really took innovative winemakers, especially in Italy, to prove that these clay vessels could make more than traditional, rustic wines. People like Elisabetta Foradori and Giusto Occhipinti really established the idea that amphorae wine could create pure, elegant expressions of terroir. These are some of my favorite wines from anywhere, and the most curious and some of the best winemakers in Spain are taking note. We just started using them in a project I’m involved with in Conca de Barberà with Tomàs Cusiné & Xavier Cepero, Cara Nord. Ester Nin is now using them for some of her wines in the Priorat as is my wife, Daphne at Clos I Terrasses. Every time I’m in Spain I see more and more amphorae in the cellars I visit.

New amphorae for Cara Nord

At what price level does it become more difficult to sell Spanish wines?

As you near $50 a bottle it becomes increasingly difficult to sell Spanish wine in the US, except in the largest urban markets. Certain blue-chip estates with universal regard sell without much difficulty such as Hacienda Monasterio or Aalto. But even in places like New York, Boston or San Francisco however, you still need people to champion these wines and as distributors merge and consolidate import portfolios, it’s becoming more difficult to reach consumers with some of our newest and most exciting wines. It’s odd that just as consumers are becoming less risk adverse, many distributors, restaurants and retailers are becoming less willing to take risks.

What can be done to change this?

Many things. Over the course of several years I’ve conducted seminars or suggested parings for guest chefs at Blackberry Farm, a renowned Relais & Château food and wine destination not far from my home in Charlotte North Carolina. At these events I’ve found that I can sell a significant amount of my allocations of the most expensive wines in my portfolio to just 20 to 40 interested and engaged wine consumers, so I know the market is present for the best wines of Spain regardless of price. In many ways this is the model that Quim Vila has created in Spain and I’m convinced is the model needed in the US – speaking and selling directly to consumers. But I cannot be everywhere at once, so I’ve invested in having talented people in key regions of the US. Not only is it the largest sales team I’ve ever had, but it is probably one of the best in the US in terms of passion and knowledge. Combined with a new website, I can directly reach as many customers as possible.

You’ve described four broad categories of Spanish wine imports, do you appreciate one over the other or think one is more important than another?

I love being in all four areas of Spanish wine imports: value wines, Rioja, the wonderlust/wanderlust arena as well as representing some of the most iconic wines of Spain. All of these categories of Spanish wine are important to my company. The value wines allow us to reach the greatest number of consumers in the US, which in turn allows us the opportunity to present the rest of our portfolio.

Garnacha Blanca in calcareous sand – Herencia Altes, Terra Alta

Do you see a conflict between representing large-volume producers alongside smaller Spanish estates?

I see no conflict between my larger volume, widely distributed wines and smaller production, estate wines as long as they are both made from indigenous varieties, are sustainably farmed and respect the place from where they come. We do not have separate standards for allocations in pallets, cases or bottles. Take for example a wine I helped to create, Evodia. It’s made entirely from fruit grown on schist in some of the highest elevation vineyards in Calatayud. I’m proud to have my name on the back label of every bottle imported to the US. Likewise I’m also excited about Herencia-Altes in Terra Alta or the wines of Jose-Maria Vicente in Jumilla and Castaño in Yecla. Just because there is volume at a property, doesn’t mean that the wines are not to the same standard of quality I expect from the latest amphora wine from Ester Nin or the minuscule quantities of Sorte o Soro I receive from Rafa Palacios or Mirando al Sur from Olivier Rivière.

Godello vineyard on sandy granite – Rafa Palacios, Val do Bibei of Valdeorras

Are wanderlust wines a new phenomena?

When I started importing Spanish wines there wasn’t much of a market for wanderlust wines. Many hadn’t even been created yet, or of they had, they were not being drunk in Spain outside of the villages where they were being made. As recently as the 2004 edition of John Radford’s, The New Spain, he commented that Valle de la Orotava in the Canary Islands had little reason to make wines worthy of export and now we have Suertes del Marques! This is just one example and there are countless more.

There is an interesting parallel in many regions of Spain – it sometimes takes an outsider to challenge a region and in the process they become insiders. There are Daphne, Rene and Alvaro in the Priorat and later Dominik Huber… Rafa Palacios in Valdeorras, Peter Sisseck in Ribera del Duero, Olivier Rivière in Rioja. Many of these people started out making wanderlust wines but overtime became standard bearers for their appellations, or in the case of the Priorat, started a revolution. In the Priorat it was literally from Co-op to Cult in a few short years. All these bursts of creativity, renaissances and revolutions are very intriguing to my customers. People like to have the sense of discovering something new.

Olivier Riviere in Rioja Alavesa

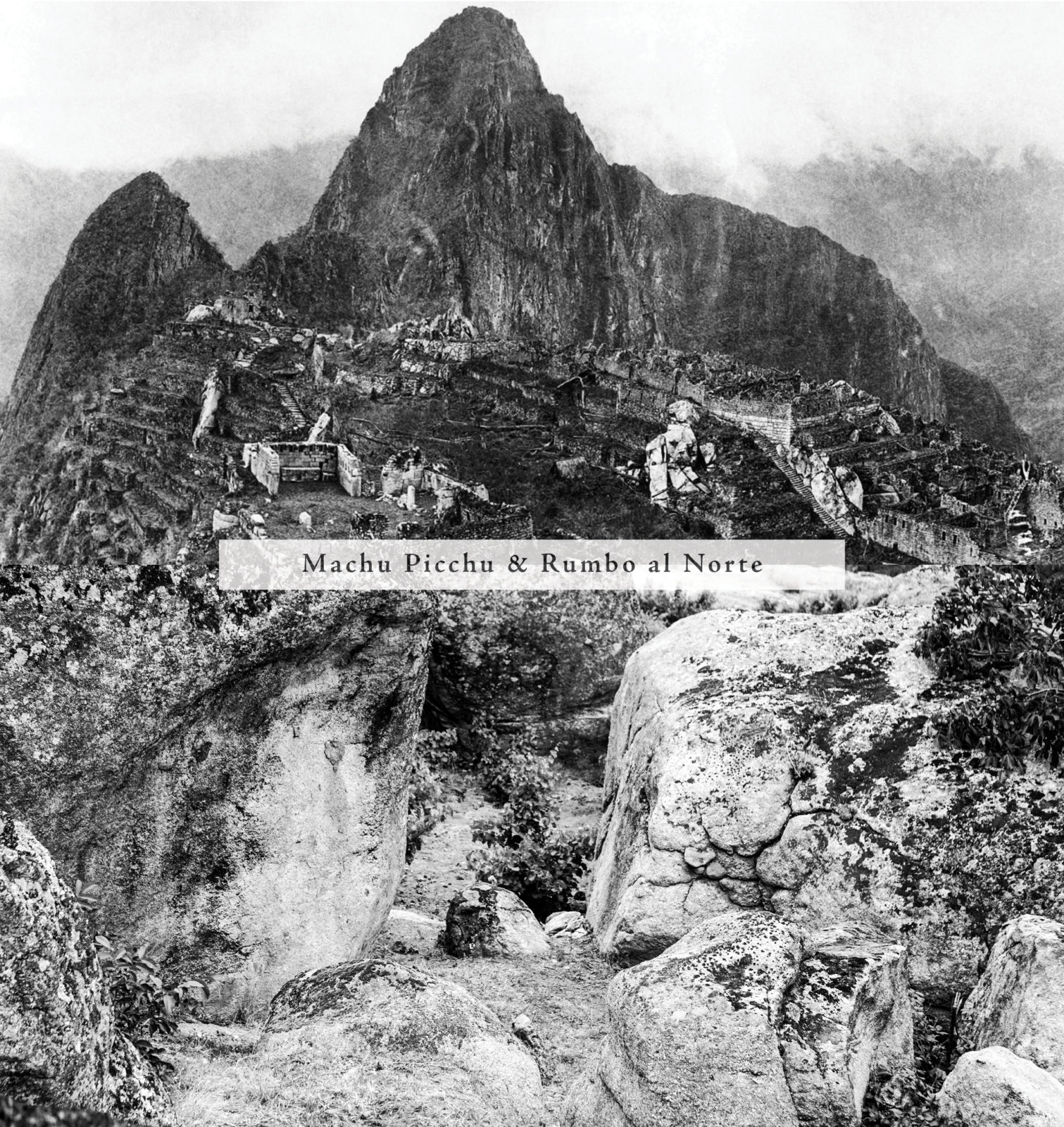

Are outsiders still important?

To a much lesser extent, yes, but as much as indigenous varieties are important, so is indigenous talent. Take for example Dani Landi and Fernando Garcia in Gredos. When I first met Dani, he was working at his family’s winery in Méntrida and long before anyone was talking about Gredos, I tasted some amazing examples of Garnacha that Dani and Fernando were making from remote mountain vineyards. It was déjà-vu all over again, because I had the same excitement when I tasted the early examples of wines from the Priorat which in turn echoed my excitement the first time I tasted Marcoux, or the old-vine Grenache at Janasse which would eventually become Chaupin. Just as thrilling as tasting these wines, is seeing where they come from. I like to joke that Dani and Fernando are modern day versions of Hiram Bingham – the first outsider to gaze upon Machu Picchu. Rumbo al Norte even resembles Machu Picchu or Stonehenge. Finding sites like Rumbo or Tumba del Rey Moro is just like the story of Hiram finding a lost Incan city – talking to the local residents, hearing a rumor of an old abandoned site, spending weeks, if not months, trying to track it down, and bringing it to the attention of the outside world.

Machu Picchu & Rumbo al Norte – separated at birth?

What about outside ideas?

I love having the opportunity to expose Benoit Droin, a vigneron in Chablis to Godello and I love that I now have Châteauneuf-du-Pape producers talking about the Gredos and visiting the Priorat. The cross fertilization between growers in my portfolio is gratifying to see.

You could say that Garnacha is in the DNA of your company?

Yes but it wasn’t because I went searching for it. I just kept stumbling across it and each time I rediscovered Grenache, Garnacha, Garnatxa, it was different. This is why in an interview several years ago for Food & Wine Magazine I was quoted as saying that place is always more important than process. That statement stuck a chord with many of my customers and became the motto of European Cellars.

Do you see a strength in representing both French and Spanish wines in the US?

Consumers in the US had come to trust my French-trained palate and grew to trust the selections of French wines I brought to the market. It wasn’t always easy because I was never interested in what my competitors were doing at the time. I never really did much with Bordeaux or Burgundy or any of the other regions of France that were well established. I fact I used to joke that the original motto for my company should have been “unknown and unsold.” But over time I began to make inroads with retailers and restaurateurs and in the process gained the attention of the press. Just as consumers were beginning to trust my French selections I began importing Spanish wines. Luckily my customers followed me there and allowed me to be one of their guides.

How do you feel about the future for Spanish wines in the US?

I couldn’t be more excited. I believe the next ten years will be the best for many of the reasons I’ve mentioned. There’s a convergence of new, fresh talent, a willingness to question conventions, and a desire to rediscover lost varieties and long-abandoned vineyards. Much of this is embodied in the Manifiesto Club Matador, which is an important first step. It has taken me 26 years of hard work to have an overnight success selling Spanish wines in the United States, but I’m confident that the best is yet to come.