This is the fourth in a series of interviews of our growers by wine writer, scientist, and critic Dr. Jamie Goode. You can also find his video tasting reviews of the wines mentioned in this interview by subscribing to his Instagram feed @drjamiegoode or our own @ericsolomonselections where they will be reposted. If you are curious to know more about one of our growers, drop us a line. To learn more about Domaine Lafage you can read about their estate on our website, and follow them on Instagram to see what they’re up to.

Jean-Marc Lafage

Jean-Marc and Eliane Lafage have built their Roussillon Domaine into one of the powerhouses of the region, expanding vineyard holdings and forging a line of wines that offers insight into the diversity of the Roussillon, using local grape varieties. The wines offer character and personality, and also excellent value for money. I caught up with Jean-Marc to quiz him about the Domaine, and also taste some of the wines.

Jamie Goode: I’d just like to hear your story. You have quite a lot of vineyards spanning most of the Roussillon. How did that happen?

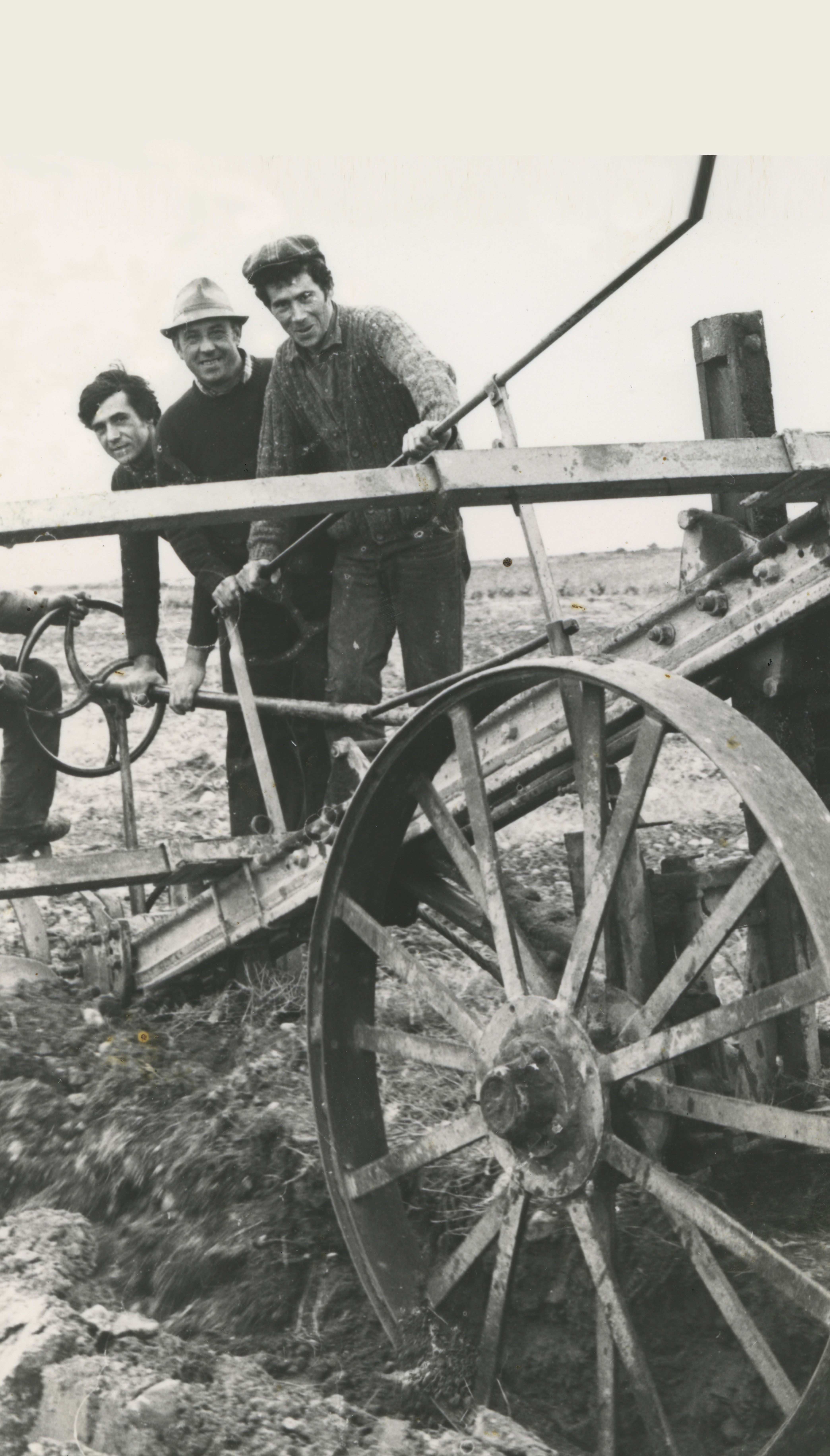

Jean-Marc, his father & grandfather

Jean-Marc Lafage: I come from a producer family. My family is from Maury, which is a place located in the Pyrenees at about 30 km from the sea. The story changed when my grandfather moved to Perpignan. At the time Maury was making a lot of fortified wines that were selling like crazy, and the price of the land was very high. Vineyards were much more affordable near Perpignan. My grandfather had four kids and all of them wanted to become winemakers, so he decided to move to Perpignan where they could afford something bigger, instead of something small where they’d be working too close together.

So the family moved to Perpignan and I came along 40 years after. I got a diploma from Montpellier and started traveling with Eliane. We worked a bit in California with the research plant of Gallo. After we went to Australia and worked in a few wineries, including Brokenwood, Mitchell, Crabtree, and De Bortoli. We also did some vintages in South Africa (this was a partnership with Hugh Ryman, Michael Fridjhon, Norma Radcliffe, and Ken Forrester), and ten vintages in Chile. We worked in Italy and Spain too, and I still do some consultancy at Capçanes in Monsant and Bodegas San Alejandro in Calatayud. So we were quite busy.

Every time we came back to our place in Perpignan we saw the sea, the mountains, and very old varieties (Grenache Blanc, Grenache Gris, Carignan Blanc, Carignan Noir, Macabeo). So at one stage, we decided to stop moving so much to be a bit more focused.

Eliane and I took over from my father when the vineyard was about 25-30 hectares, and we decided we didn’t want our winery in the middle of the vineyard. The Roussillon is really diverse: within 50 km you can have vineyards at 600 m or you can have them touching the sea, and the soils vary from pure black slate, limestone, clay to chalk. So we tried to explore our place a bit more. Today we have vineyards in seven different places, which is quite difficult – in terms of viticulture it’s much more challenging than having the vineyards around you.

Since the beginning our strength has been having very good quality, but also affordability. We try to have a quality-price ratio that works well in the market.

How did you get to where you are today?

In 2001 we really decided to push things a bit, and 20 years later we are selling wine to 40 different countries. We have a new winery and bottling line and we have a good set up of facilities for trying to make the wine as well as we can. We have five enologists in the company, two engineers, and we try to be focused on the quality of the place.

The winery is very well designed. It’s designed to respect the grapes. We bring the tanks into the vineyard, we pick the grapes, put them in the tank, bring them back to the winery. Afterwards we have a crane which moves the tank in the winery. We try to be as pure as possible.

Do you use a sorting table when you fill the tanks in the vineyard?

It depends. We have 50 people for two months, with a sorting table in the vineyard. We also pick by machine with the latest technology, doing a very great job. The machine has its own sorting technology.

Which one do you use, Pellenc?

Yes. We also buy some grapes from friends, and they can use Pellenc or New Holland. The latest models. The two are very similar. For the best, best results, I like the Pellenc.

So you are basically getting whole berries?

Yes, that is the point. You have full berries in your hopper, you take it with the crane and empty it into a bigger tank to ferment, and this allows you not to have any kind of pumping. For red wine, we don’t pump anything. For white wine and rosé wine, we prefer to pump because it enables us to chill the grapes. The vintage starts around the 7th of August and the temperature can be very high. When we work in August we work at night, or early morning. The temperature can get up to 28 C, so we chill the grapes to around 5 C. An at the same time we put carbon dioxide into the pipes to make sure the grapes are not going to get any kind of oxidation. For white or rosé, the grapes aren’t going to see air. This is a sunny climate and the acidity is medium to low, so we have to be very careful about oxidation. You can lose much more than you can gain by having the juice oxidize. I had been making wine for La Chablisienne in Chablis for 10 years, and there we were oxidizing the juice because the pH was low and the acidity so high. It was better to oxidize the phenols and make the wine a bit rounder. Here we are not in the same conditions so we are playing in a different way.

Do you use the Inertys system to protect the must during pressing?

Yes. We have one Inertys which we use for the white and rosé.

What is your vineyard area now?

We have seven vineyards and each of them must be between 20 and 50 hectares. We should be around 200 hectares.

And you went back to Maury and bought Saint Roch: is that recently?

And you went back to Maury and bought Saint Roch: is that recently?

That was in 2008. My father grew up near Saint Roch. His parents had some land near there. All my life I heard about the good wines that Maury was making in a very natural way. So I wanted to come back to our home. In 2008 we had the opportunity to buy Saint Roch and we took it. The vineyard at the time was in poor condition, but we have been working on it constantly. We have established a nice winery there where we only make red wine. We don’t make white or rosé there because the winery at Lafage is much better equipped to make white and rosé.

What’s the situation like in the Roussillon overall at the moment? Are there many producers doing the sort of thing you are doing? Is there a natural wine scene emerging?

Not really. There are a few young people moving a little bit. But 80% of the grapes still go to the cooperatives, and most of the cooperatives today are suffering because of the way they do their business. Most of the time in France when you are a Cave Cooperative you sell your wine to a negociant. Normally, they never develop their own brands. In France, the exceptions would be La Chablisienne, Nicolas Feuillate or Tain L’Hermitage and some others. There are maybe 10 cooperatives in France doing a really good job, going from the grapes to the glass. Most of them are selling the wine in the bulk market, which means a price for liter, and while in the Languedoc or Gascony maybe you can have 15-20 000 liters per hectare, in the Roussillon the average is about 3000 liters per hectare. So whatever price the coop is able to sell for, they never feed the producer.

The Roussillon has around 17 000 hectares and we are losing some of this when people retire. It is very difficult to find people to take over. I think this is helping us a lot because we have the market, we have the product, we needed more product, and we have been able to buy grapes from nice producers, to make wine in nice co-ops, and also to rent vineyards. Today, maybe 5 or 10 vignerons from the Roussillon are doing well, maybe another 10-20 are doing OK, and then after this, it is quite difficult. With this kind of yield per hectare, it is very difficult to make the business work.

There are interesting terroirs, and presumably, you want to be making high-end wines from them. This is not a place for bulk wine. I imagine the viticulture is expensive.

Yes, there are a lot of old vines and bush vines, which are fantastic. At the end, the cost of production will be the same as St Emilion. Even an average St Emilion or Haut-Medoc will be less expensive to produce. When you talk about these small producers, they are not really going to the export market. But the French consumer is very old-fashioned and most of the time will prefer to buy St Emilion or Haut-Medoc than taking the risk of going to the Roussillon. Things are changing. It is not like 20 years ago. But still, it is very difficult to compete at a high level of price.

When did you take over?

I started in 1996 and really decided to travel less and be more focused in 2002.

Have you changed your approach to farming?

Yes. My father had just one vineyard around his farm. After, when we started developing newer vineyards, some could be organic in a very natural way, and some others are near the sea with sea breezes every day where if you go organic you have problems with botrytis and mildew. So you have to adapt your viticulture to each plot. I love organic wine but we cannot make organic wines in all the places. What we want is to be able to pass the soil to the next generation in a clean state. We don’t just want to be organic but develop many kinds of tools making the vineyard greener. We plant trees around the vineyard; we plant grasses in the vineyard to avoid using fertilizer. We have put some bat houses in to reduce the insect pressure. We are doing many things like this. ‘Organic’ is maybe a simple way to talk about wine. It is very restrictive and it doesn’t lead you to being better and better. This focus can be very good in some vineyards: we have some vineyards near Maury in a very windy place. The tramontane is blowing all the diseases away, and in this case, just having a bit of sulfur and a bit of copper can be fine. But as you know copper is very bad for the soil, so you have to be very careful. You have to play with many tools.

So you believe in more scientifically rational viticulture, that is looking to preserve or increase soil health, and is applied intelligently to each terroir?

It is more agroecology, I would say. In some we do agroforestry, in some we do permaculture. We have 60 hectares with irrigation, but for this one we have some special machine we put on the vine trunks to look at the sap movement, so we know whether to water or not. We are well followed by the French government because we are experimenting with this, and we have shown them that most of the people are using 1000 m3 per hectare, for growing grapes. For example, last year we did 50 m3. The most we used was in 2019 which was 600 m3, in a year when most of the people used more than 1000 m3. Sometimes it is good to irrigate the vineyard. When it is too dry the plant gets stressed and the energy still remaining at the end is the grapes. The plant takes energy from the grapes to survive. If we can help the plant a bit with a few drops of water, it is better to do it. But every time we decide to do something we have to prove why we want to do it, and always thinking about the agroecology concept.

Winter cover crop at Domaine Lafage

What sort of cover crops do you use?

We use a lot of fava to put some nitrogen into the vineyard. We use triticale because we have a few vineyards with a bit of clay. We are happy having a bit of clay because 90% of the vineyard doesn’t have irrigation. Clay can be bad because it tends to be vigorous, but 10-15% of clay can be good because it retains water in the soil, and when the weather is very dry in August and September, the water still there. Triticale in a clay soil allows it to have more aeration, which results in more life in the soil. We also use mustard and a few grasses. It depends on the place.

Are you happy with the varieties that you have? Or are you trying out varieties not from the region?

We have 80% of the vineyard planted with Grenache Blanc, Grenache Gris, Grenache Noir, Macabeo, Carignan, Mourvèdre, Muscat, and other local varieties. We have also planted some Durif, Touriga Nacional, and Mencia. We are planting varieties well adapted to difficult conditions. This year we have planted 2 hectares of Durif, 2 hectares of Touriga Nacional, and 10 hectares of Carignan. We know that we are not going to be able to irrigate all the vineyards, so we have to be able to farm without water additions. Green fertilizers are good; a very good rootstock is good; a very good vinifera variety that is able to survive our conditions of high temperatures and a lot of wind is good. Grenache is a perfect example. We have wind in the Roussillon once every three days. The tramontane can be from 50-120 km/h. Grenache is like bamboo: it bends in lots of ways but isn’t damaged. With Syrah, it is much more difficult, as is Vermentino.

Do you have to trellis them?

Yes, but even when you trellis, the better thinking is to have them in a place that’s sheltered from the wind. We might grow trees around the vineyard to protect them, for example.

The effect of wind on vines in Maury

Is wind ever a good thing?

It depends: wind in April can be a disaster. The shoots are 20-30 cm long and if you have 100 km/h wind you can lose 70% of the crop. After, wind can be good because we don’t have a problem with mildew or botrytis. But if we have too much wind in summer, it means more transpiration from the leaves so we need more water. It is all a balance.

Which of your wines are your favorites?

We say that we like all our wines, and after this there are some wines with a bigger identity than others. For example, we have a cuvée Léa coming from Côte du Roussillon Les Aspres. This is located in the Pyrenees at 350 m near the Spanish border. The soil is very poor, and the vineyard is terraced, with very low vigor (2.5-3 tons/hectare). This wine has very pure fruit with low pH and high acidity. It is much more like Burgundy style but with more power. And there is Chimères, which is Château Saint-Roch from Maury. This is at 100 m with black slate soil, and the wine is much more powerful. These are two different kinds of wines: one is Burgundy style and the other is like a big Haut-Médoc.

You are working with different soil types. Can you relate the soil type to the flavor of the wine?

We are located in the Pyrenees, so we have many different kinds of soils. 80% of our vineyards are planted with four varieties. When we taste blind, sometimes we can see where the wine is coming from, but we can’t tell whether it is Grenache or Carignan. The soil impacts the wine. Even just the color is affected by the soil. A wine from Les Aspres, for example, has a low pH and the color is always brilliant. In Maury, the fruit flavor is more black fruit than red, and the color doesn’t have this brilliance. The different places have different aromas. When we were younger, we wanted to have different places to try and make the best wine altogether, blending them. But that’s like trying to blend a good Bordeaux with a good Burgundy. It is almost impossible: it might sound like a good idea, but it doesn’t work. Here, with the same variety, if you start adding a bit of wine from Maury into the wine from Les Aspres, you kill Les Aspres. When you do it the other way, you make the wine from Maury a bit lighter, but it’s not what you expect from Maury. From doing three wines 20 years ago, now we make 25 wines, for respecting the place. It makes our work a bit more difficult.

I’m a strong believer in soil affecting flavor, and someone like you is in an ideal position to see that because you have different soil types. This is part of what makes wine so interesting.

It is not just soil. It is soil, elevation, and exposition. In a blind tasting, you find it, when you are used to your place.

Domaine Lafage Centennaire 2019 Côtes Catalanes, France

Domaine Lafage Centennaire 2019 Côtes Catalanes, France

13% alcohol. 80% Grenache Blanc and Gris, and 20% Roussanne from old bush vines (95-100 years old) planted in Canet en Roussillon near the sea. It’s harvested in two lots: one is picked earlier and then barrel fermented in new French oak (30%), and then the remainder is picked a bit later and fermented in stainless steel. The result is a beautifully balanced harmonious white, offering textured pear, white peach and citrus fruit. There’s a faint saline note here, and also some crushed rock savouriness, as well as rounded fruit hemmed in by nice lemony acidity, expanding on the finish. The oak has integrated beautifully with fine spices the only contribution. Very sophisticated and great value (UK retail c £12). 94/100

Domaine Lafage La Grande Cuvée Blanc Côtes Catalanes, France

Domaine Lafage La Grande Cuvée Blanc Côtes Catalanes, France

13% alcohol. 70% Grenache Gris, 20% Grenache Blanc, 10% Macabeu. Schist soils, 300 m altitude, east facing. Old vines (80 years) barrel fermented in 500 l barrels. This is fresh and complex with finely textured pear, apple and white peach fruit with some notes of fennel and toast, as well as a hint of lime and vanilla, adding freshness and a touch of sweetness. It’s a layered, complex white wine with finesse and elegance, set up for a long life. It’s delicious now, but has such potential for development. Just fabulous. 94/100

Domaine Lafage Nicolas Vieilles Vignes de Grenache 2019 Côtes Catalanes, France

Domaine Lafage Nicolas Vieilles Vignes de Grenache 2019 Côtes Catalanes, France

15% alcohol. Enticing and fresh with sweet cherry and berry fruit with notes of pepper and herbs, this shows great concentration but also finesse. It’s more red fruits than black, with some structure and a fine green hint that adds brightness, and no noticeable oak. This is all about wonderfully pure, concentrated fruit, showing Grenache off in its finest light. So supple. 93/100

Domaine Lafage Léa Les 20 Ans 2018 Côtes du Roussillon Les Aspres, France

14.5% alcohol. This is the 20th vintage of Cuvée Léa. The vines are at 300 m in Les Aspres (in Maury) with schist/marble soils. There’s 60% Grenache and 20% Carignan (both 80 year old vines) and 20% younger Syrah. This is fermented in opened up 500 litre barrels. This is supple and fresh with a savoury, slightly cedary edge to the sweet cherry and plum fruit. It’s really appealing with ripe fruit and some liquorice and herb notes. Very stylish with a bit of grunt, but the dominant theme is sweet, pure black fruits. 92/100

Domaine Lafage Narassa 2018 Côtes Catalanes, France

15% alcohol. 70% Grenache, 30% Syrah. This is a distinctive wine. Back in 2015 Lafage forgot a plot of Grenache and ended up harvesting it at 17% potential alcohol. Because of the high sugar, fermentation stopped with around 10 g/l sugar left, so they blended in some fresh 12.5% Syrah from a high altitude vineyard to give balance, making a Ripasso style. A portion of the blend was matured in sweet Maury barrels. The result is a rich, generous, textural red wine with some cedar and spice notes under the sleek cherry and berry fruits. It’s very rich and generous, and so smoothly textured with some spice and herb and medicine notes on the finish, adding a foil to the sweetness. A really distinctive red, with all the warmth of the south. 91/100

15% alcohol. 70% Grenache, 30% Syrah. This is a distinctive wine. Back in 2015 Lafage forgot a plot of Grenache and ended up harvesting it at 17% potential alcohol. Because of the high sugar, fermentation stopped with around 10 g/l sugar left, so they blended in some fresh 12.5% Syrah from a high altitude vineyard to give balance, making a Ripasso style. A portion of the blend was matured in sweet Maury barrels. The result is a rich, generous, textural red wine with some cedar and spice notes under the sleek cherry and berry fruits. It’s very rich and generous, and so smoothly textured with some spice and herb and medicine notes on the finish, adding a foil to the sweetness. A really distinctive red, with all the warmth of the south. 91/100

Saint-Roch Chimères 2018 Côtes du Roussillon Villages, France

Saint-Roch Chimères 2018 Côtes du Roussillon Villages, France

15% alcohol. This is from the Agly Valley at the foot of the Castle of Queribus, next to Maury. It’s a blend of 40% Grenache, 30% Carignan (these first two varieties bush vines) and 30% Syrah (trellised). Chalky clay and black schist soils. A blend of larger barrels and concrete tanks. This is ripe and expressive with sweet berry and cherry fruits, and a bit of chalkiness to the palate. It’s also a tiny bit salty. Lovely weight with nice fruit expression, some southern warmth, and lovely drinkability. Walks the tightrope between ripeness and jamminess pretty well. 92/100